Planet Earth is experiencing yet another year of historic heatwaves. This, of course, is no coincidence, courtesy of climate change.

The UK, for example, had its hottest day on record on 19 July, with temperatures hitting up to 41°C. To clarify, this means London will be hotter than the Caribbean and western Sahara.

As a result, the British government issued a ‘red extreme’ heat warning for much of England, from London to Birmingham and Manchester. This meant “widespread impacts on people and infrastructure” were expected, with “substantial changes in working practices and daily routines” required, according to the UK Met Office, which described the overall situation as a “national emergency”.

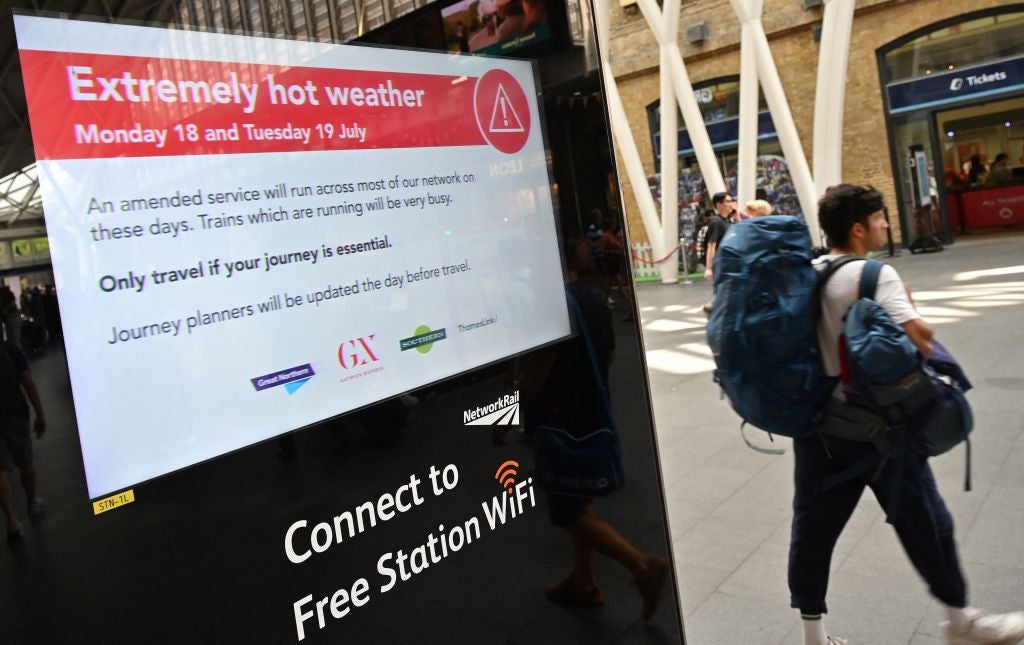

Some schools, businesses and institutions closed early, or did not open at all. Network Rail said people should travel only “if absolutely necessary”, with some train cancellations announced days in advance.

Beyond the human toll – indeed, hundreds of vulnerable people in the UK are expected to die from the heatwave – what do these temperatures mean for where and how people work?

Many European buildings are not equipped for heatwaves

Covid-19 and the shift to working from home has already dampened demand for office space. Rising temperatures will deal another blow. The current heatwave is a deafening alarm bell for the real estate industry.

Simply put, heat is making more and more buildings in Europe unusable. “The UK’s buildings and offices aren’t designed for temperatures in the high 30s [degrees Celsius], let alone the 40s,” says Chris Bennett, co-founder and managing director of sustainability services company Evora Global.

Even if British buildings have air conditioning systems, many are struggling to operate them due to the intense heat. Even prime office space such as that of the Guardian newspaper’s headquarters in King’s Cross have seen air conditioning fail to operate.

A stiflingly hot office is no place to be, let alone work. “Some [offices] will be practically deserted as working from home re-emerges,” says Bennett. “When there is such competition to get employees back into the workplace, uncomfortable offices will become devalued.

“Investors could be looking to invest in real estate assets that are easy and cheap to keep cool; for people, for perishable goods and for IT. [They will be looking for] properties that have the capacity to cope with high temperatures.”

The problem here is manifold, however, since building managers are now under increased pressure to keep their offices cool, despite very expensive energy bills and low-emissions targets.

The issue is not just limited to offices, either. In fact, social infrastructure such as lightweight residential buildings, schools and hospitals that lacks air-conditioning could be among those least adapted for very high temperatures, according to Bennett.

“We have to wake up and see this as a final warning for the real estate industry and the wider business community,” he says. “Climate change is here and is playing havoc. If heatwaves become a permanent fixture, cooling our buildings could cost more and more and create more emissions.” Of course, those emissions then contribute to climate change, thereby creating a vicious cycle that undermines the value of assets (and the planet).

“For too long, the real estate market has focused on historic data,” adds Bennett. “In the UK, no one is assessing cooling capacity, at any scale, since the focus has been on decarbonising heating. That is true across Europe, not just the north.”

In fact, southern European cities will be more exposed as they are closer to the equator, especially inland cities where hot air can get trapped, such as Madrid.

Bennet says that in Spain the cooling capacity will vary depending on the age and design of the building. For instance, Moorish architecture was designed for hot climates while more modern, sealed glass and steel offices can leave the occupants much more exposed and reliant on air conditioning systems.

Offices could become very popular in summer

On the flipside, heatwaves create an opportunity for air-conditioned office spaces to become much more attractive places to be.

“I come from a part of England that is permanently, blissfully cold but moved to London 20 years ago. I wasn’t built for temperatures of more than 30 degrees Celsius, let alone 40,” says Richard Gardham, managing editor at Investment Monitor.

“Ever since the Covid-19 lockdowns, I had settled into a hybrid working pattern, but during the recent high heat days in the UK, I was coming into the office on days when I normally wouldn’t because the air conditioning there is so wonderful. It even makes a journey on a crowded, sweaty commuter train worthwhile. If I didn’t have children, I would be seriously considering sleeping there too,” he adds.

Gardham’s sentiments are shared by many others that have the privilege of chilled office space. Rose Marshall, associate director at ING Media, a specialist communications consultancy for the built environment, says: “In our experience, staff are more inclined to come into the office during heatwaves as it is much cooler here than it is in their homes – provided they don’t have to endure long journeys on public transport. So, as businesses think about how to attract and retain staff, maintaining a comfortable environment is an increasingly important consideration.”

How to upgrade your office to cope with a heatwave

There are several ways investors and building managers can improve their sustainable climate controls.

“The drive to reduce energy use in all buildings has led to more serious consideration of passive design measures; optimisation of glazing design to control solar gains while allowing good levels of daylight, effective shading in the hottest parts of the year and thermal mass in combination with night-time cooling to help regulate internal temperatures,” explains Andrew Lerpiniere, director at Webb Yates Engineers.

“While these apply mainly to new-build projects, there are some simple measures that can be applied to refurbishment or improvement projects; exposing or adding thermal mass and enabling night-time cooling. Considering whether external shading, which has the greatest impact, may be possible,” he adds.

Passive solutions should complement air conditioning, according to Lerpiniere, who adds: “As air-conditioning systems become more energy efficient and the electricity grid becomes greener, particularly from solar energy generation during the warmer months, the carbon cost also comes down.

“As part of the switch to all-electric buildings, replacing gas boilers with heat pumps, there is an opportunity to add cooling to buildings at limited extra cost. All of these measures involve some time, effort and cost, but conditions this week should perhaps act as a call to all of us to start plotting our way to a comfortable, low-carbon future.”

While that is well and good, buildings are just one part of the equation. As alluded by Gardham and Marshall, getting into the office is another. In the UK, millions more people work from home during high heat days to avoid the severe disruption on transport networks caused by soaring temperatures.

It is clear, therefore, that if investors are going to pour money into sustainable cooling systems and buildings, government transportation infrastructure must keep pace. Without it, what is the point?