In theory, the economic relationship between Australia and China is a complementary one. Mining is structurally important to the Australian economy, currently accounting for almost 14% of gross domestic product (GDP), up from 4% in 2004.

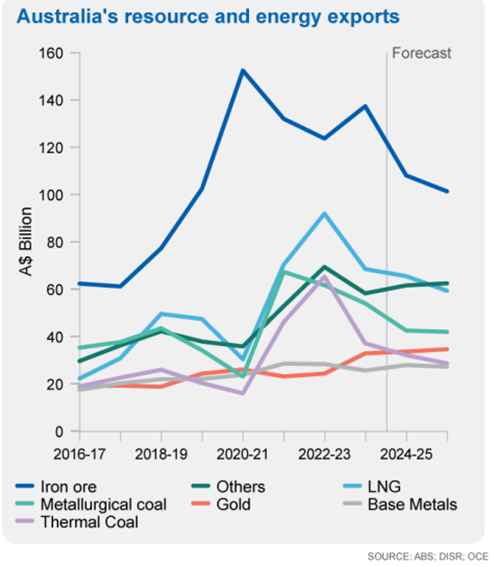

Australia exported A$673.28bn ($456.88bn) worth of goods and services in 2023, with iron ore and coal exports taking up the top two spots, accounting for 20.2% and 15.2% of the total, respectively.

While mining has expanded, manufacturing has declined, making up just 6% of GDP, down from 12% in 1992. In contrast, China’s manufacturing ascendancy continues to furnish demand for Australian commodities, proving a vital customer for the mining industry.

As many Western economies struggled to compete with cheap Chinese manufacturers over the past 20 years, the meteoric rise of Beijing was a boon for Australia’s commodity export economic model. In 2023, China was Australia’s largest trading partner, buying 32.5% of all Australian exports – but the relationship has not always been rosy.

Three years of Chinese economic coercion

In 2020, political differences between China and Australia began to hamper their economic relationship. Scott Morrison’s government called for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19, laying tacit blame on China for the outbreak, and the Turnbull Government’s ban of Huawei’s 5G network became an increasingly “thorny issue”. In response, Beijing accused Australia of aligning with the US in pursuit of a hostile foreign policy and meddling in Chinese internal affairs, subsequently stopping the import of all Australian goods. China’s imports of Australian coal fell to virtually nothing, having imported A$13.7bn ($9.4bn) in 2019.

The economic coercion was designed to break Australia into a position of ideological acquiescence with Beijing. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) didn’t like that its trading was beginning to question its politics. However, the tactic was not effective.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBeijing underestimated its reliance on Australian iron ore, which was needed for steel-making, and imports basically continued at the same level.

While China imported less coal, India and Japan doubled their consumption, proving to be reliable alternative customers. The inferior domestic coal China used as a replacement was also unreliable, leading to coal-fired power ‘brown-outs’.

In addition, Australia held a strong geopolitical bargaining position. China wanted to join a potentially lucrative free trade agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, but as a member, Australia could block China’s accession. Evidently, Canberra held more global clout than the CCP first assumed.

Return to trade

The plan for economic coercion failed, and for some commodities, Chinese imports from Australia are now as high as they have ever been. Driven by the inferiority of its own coal, China began importing Australian coal again in January 2023.

In 2024, Chinese coal imports from Australia may reach a record high, according to Andrew Gorringe, a researcher at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). However, it is important to note that only the thermal coal trade has rebounded and surpassed historical levels, while the metallurgical coal trade has declined.

Lithium is another market in which China and Australia have complementary capabilities. Australia was the world’s largest lithium producer in 2023, accounting for 45% of the global total, but lacks the ability to refine and process.

China, on the other hand, is the world’s leader in lithium refining and processing, with around a 57% monopoly. Between January and June 2023, Australia’s sales of lithium to China reached a combined value of $11.7bn. As with the iron ore trade, the Australia-China lithium trade needs fit together like a key in a lock.

The trade only lives twice?

Although trade seems as good as ever, there are reasons to suggest this may not continue.

The coal and lithium export business model may have an expiry date determined by external forces. China is looking to limit its demand for coal, with Xi Jinping pledging that coal use will peak by 2026. Regarding thermal coal, Gorringe points out that Beijing drastically reduced approvals for new plants in the first half of 2024 (H1 2024), with just 9.1GW of coal-fired capacity given the go-ahead, 83% less than in H1 2023.

“This will add to the current momentum whereby grid-connected wind and solar capacity exceeded that of coal for the first time in June 2024,” he says.

On the metallurgical coal front, China did not approve construction of any coal-based steel plants in H1 2024. Instead, it approved 7.1 million tonnes (mt) of new, cleaner scrap-based steel production capacity using electric arc furnaces, according to Reuters.

While China is looking to reduce overall demand for coal, it also wants to produce more supply domestically. According to Global Energy Monitor (GEM), China has more than 1.2 billion tonnes of coal mine capacity in the pipeline, more than the rest of the world combined. Around a third of these mines are under construction and will soon be operational. Most are mega-mines with lifespans of at least five decades.

“In the long term, the declining demand for coal and reduced reliance on imports will place Australia’s already declining market share under more pressure,” Gorringe says.

Owing to such pressures, the Australian Government says that despite the coal trade with China resuming, Chinese imports are in structural decline, and that the country’s domestic coal supply could match domestic coal consumption by the 2030s.

Taking charge of Australian lithium supply

At first glance, the lithium trade seems more solid and structurally entrenched. Australia provides 60% of China’s lithium demand and Chinese companies such as Ganfeng Lithium have invested long-term capital in the industry.

However, the US is encouraging Australia to dilute this relationship. China has a stronghold on global lithium supply chains and Washington is keen to put a stop to this. It offered Australia access to its $369bn Inflation Reduction Act clean energy incentive if domestic companies have less than 25% ownership, voting rights or board seats held by “foreign entities of concern” such as China.

This isn’t just Washington barking orders. Canberra recognises it may have to realign in favour of the US. Under the Critical Mineral Strategy 2023–2030, the Australian Government aims to increase collaboration with “like-minded” partners such as the US, the UK, Japan and the EU.

Since 2021, A$1.5bn ($1bn) in financing has been offered to “strategically significant projects” that reduce reliance on China. The Australian Government has also agreed to support supply chains with the US while blocking several Chinese investments.

In practice, this resulted in Treasurer Jim Chalmers blocking two proposed Chinese investments in Australia’s lithium sector over the past two years.

However, such aggressive decoupling does pose risks for Australia. Premier of Western Australia Roger Cook said last December: “It is more a matter of accepting the fact that it’s not whether they [the Chinese] will come but that they are already here. We have to understand that China is our biggest customer and our biggest supplier of a lot of the elements of a critical minerals and battery supply chain.”

Australia currently does not have any of its own lithium processing facilities, which take a long time to construct. For instance, a new local lithium hydroxide plant in Kwinana, Western Australia, took five to six years to start operations. The Chinese company Tianqi Lithium invested A$700m ($482m) into the operation in 2016, and other similar projects will require Chinese capital.

What is next for China-Australia mining trade?

Despite the thawing of Australia and China’s relationship and the return to prosperous trade, Canberra needs to be aware that the current state may not last for as long as it hopes.

Demand for coal could soon enter structural decline, with China aiming to use less for power generation and produce what it does use domestically.

The lithium relationship should be more solid as China is heavily invested in Australia’s industry, but geopolitical manoeuvring on both sides could still destabilise it.

If Australia has learnt anything from the three years of economic coercion, it will know not to rely on one trade partner too heavily.