“We need to go to China, everyone else is doing this and if we don’t move fast we’ll be left behind and our competitors will reap the profits and market share.” This has been heard myriad times in many boardrooms. Or for another variation, there is this plea to consultants: “Provide us with a justification to go to China, India or any other emerging market so we can keep our board and shareholders happy and our costs in control.”

Do you still remember the rush to many emerging markets in the 1990s? What happened after many of these companies went to China? Have all of their foreign direct investment (FDI) projects been successful, have they been profitable, and have they met the expectations?

Did the China charge pay off?

The roaring 1990s was the decade of globalisation and the exponential growth of FDI projects to emerging markets. FDI numbers doubled, often driven by cross-border mergers and acquisitions. China became the “factory of the world” and India the main destination for business and IT outsourcing. For many companies, FDI was not an option or choice, but a necessity.

Many boardrooms put teams in place to explore potential new growth markets, either to find consumers or to decrease their operational cost base. The corporate teams were often put under time pressure to produce the results and conclusions that would justify the next FDI adventure, which is often a recipe for a disaster. FDI is not a necessity, and if set up for the wrong reasons it will not be profitable. Even if there is a huge foreign consumer market looming, FDI may sometimes not be the best channel to enter the foreign market.

Other reasons to justify FDI that are often heard are “our competitors are doing it”, “our domestic market is saturated”, “we need to be in those profitable markets before others”. These are all motives that can signal red flags for an upcoming FDI project.

Beware the FDI risk

FDI projects are high-risk ventures for all companies. Even the larger, experienced multinationals struggle to undertake them successfully. On top of this, FDI is often the highest level of commitment from a company to a new foreign market. It involves a large capital investment in a new, unknown business environment, a large commitment in management time, and often the profitability is insecure and may only be realised after two or three years.

Building a solid business case and rationale for the FDI project is essential and is the foundation for the strategy. Questions to consider are:

- What are the reasons for contemplating an FDI project?

- Is it part of our long-term corporate expansion and growth strategy?

- Are there no other means to reach the objectives we have – i.e. exporting from neighbouring markets or finding a local partner?

- Which markets are we potentially considering?

- Where are the potential challenges, risks and opportunities?

- What are our peers within the industry doing?

- Is this the right time?

- Do we have the resources and time to manage this? (An average FDI project takes on average between one and two years from the thought stage to the implementation stage.)

- What are the boardroom expectations of this project?

- Are the expectations reasonable in terms of profitability and time frame, and are there any underlying motives or hidden agendas we are not aware of? For instance, is the CEO the main supporter due to personal or career ambitions?

- How big is the support among the entire board, and who is against the project and why?

A clear and transparent presentation of the project to the board is the best way to find out what the expectations are and how much support there really is for the project. If the company is large enough, the team working with you should be diverse and from different disciplines and departments within the company. Think, for instance, of setting up a project team consisting of an engineer, someone from tax or finance and from HR and operations, and last but not least, a resourceful and creative project manager.

In addition, compose a team that has experience in the international strategy of the firm or has a cultural background in the target market or country and speaks the language. Make sure the diversity of the team composition is taken into account – not only is this helpful from a UN Sustainable Development Goals perspective, but a good gender balance also benefits the overall project’s success and negotiation power. Many studies have shown that women and men have very different perceptions towards taking and managing risk, which can be important to an FDI project.

Once your strategy is defined and supported by the board, and the time frames, expectations and project parameters are clear, you can start doing your due diligence and explore an initial long list of approximately 10–15 locations, of which between three and five will be shortlisted based on the critical knock-out criteria and specific benchmarking techniques.

Often the process of elimination from a longlist to a shortlist is done through a high-level analysis of macro-economic data or exploring numerous business environment indicators from international organisations and consultancy firms that publish rankings of the most competitive business environments. There are currently more than 50 country-level competitiveness indicators, but be careful as in many cases the indicators published are often based on the same set of data and it is the methodology underlying the indicators that is the only difference.

It is also good to emphasise that regional/sub-national (or city-level) differences within and among countries can even be larger than differences in business environments among countries. Data at city or sub-national level can often be obtained by national investment promotion agencies, with whom it is advisable to work. Make sure the data is correct, up-to-date and from reliable sources, but remember that emerging markets data and information is more scarce, often dated, and not always as reliable as data on developed markets. This is particularly true when it comes to labour cost information.

The site visit: avoid getting lost in translation?

When the shortlisted sites have been selected and analysed, it is then time to start organising site visits and making travel arrangements. The site visit is, in fact, the due diligence that qualifies the desk research on the specific locations and helps the potential investor to understand and feel what it is like to operate in this location. Often, most of the members of the project team, preferably complemented by someone from the region or country being visited, will travel to all of the shortlisted locations and explore potential sites, as well as meet government officials, real estate brokers, and other foreign firms operating in the location.

The site visits are typically scheduled with a Western focus on managing agendas. In many cultures you will be met with amazement when they hear your site visit schedule, and they will feel sorry for you having to jump from one meeting or airport to another without having the time to learn more about the country or its culture. It is advisable to give yourself additional time for unscheduled last-minute meetings, which can be decisive. Think about holding meetings to better understand upcoming infrastructure developments or cancellations in road networks – topics that are often overlooked.

The site visit will also typically be your first encounter with the new business culture in which your company will be operating. Allow yourself the mental space to understand that things work differently in other countries and perhaps even see more opportunities. Don’t take everything for granted, and challenge unclear information. Meetings are often organised at the last minute, are chaotic and not to the point, and characterised by cultural differences and language difficulties. The meetings often reflect what you will encounter during the future implementation of the project. Meetings with government officials are also often scheduled at the last moment, cancelled at short notice, and seemingly perceived as not particularly important, despite the country’s eagerness to attract investment.

There is also a big difference between the language that government officials use and the terminology used by corporate executives. Government officials speak of the economic development impact of the new potential FDI project or job creation, while executives speak of profitability and the need for a highly skilled and experienced workforce. Often both parties mean the same thing and have the same objectives and goals, hence it is good to take time to imagine yourself sitting at the other side of the table and build a good relationship with the project supporters in your future FDI destination.

After the project team has returned home, you should then organise a few team meetings and digest what was discovered, discuss the outcome of the site visits, and identify the challenges presented by each location. In your next board meeting it is important to define the risks associated with the project in the locations, but also highlight the opportunities that may not have been apparent prior to the project initiation and site visits.

The above suggestions are obviously not exhaustive, but they will help to prevent your next FDI project from turning into a nightmare, and allow you to get a better night’s sleep as you dream about international expansion.

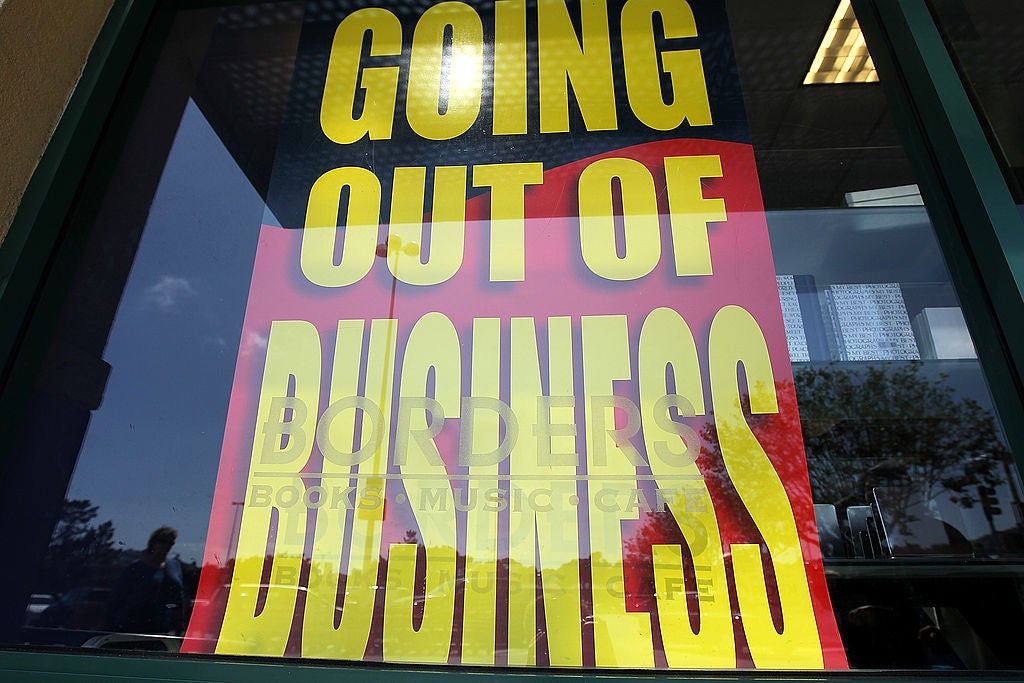

Homepage image by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.